|

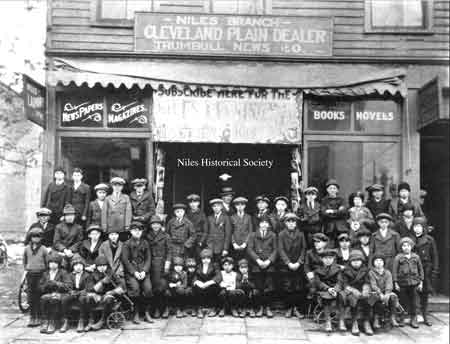

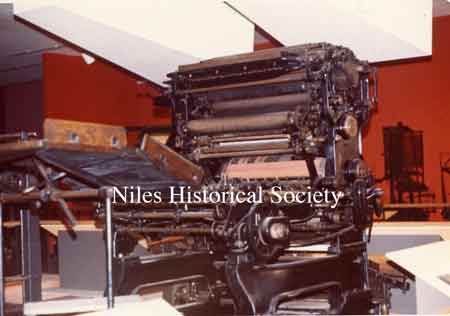

A Glimpse at the Harris

Brothers and their Press.

In 1976 the predecessor of Harris

Automatic Press Co. of Niles, Ohio, Harris Intertype Co. of Cleveland,

Ohio, donated the first automatic feeding press designed and built

in 1896 by Charles and Alfred Harris to the

Graphic Arts Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington,

D.C. Most Nilesites have heard about Alfred and Charles Harris

and their invention of the first offset printing press; but the

story, as written by a family member, recently surfaced.

In 1931 A.F. Harris, son

of Alfred F. Harris, then president of Harris Seybold-Potter

Co. of Cleveland, wrote a story for Graphic Arts, a monthly magazine,

which I’d like to quote:

“ Many people recently by

reason of the fact that this is the twenty-fifth anniversary of

the building of the first commercially successful offset printing

press, have asked me to tell them the story of the discovery of

the offset by my father, A.F. Harris, and his brother, Chas.

G. Harris."

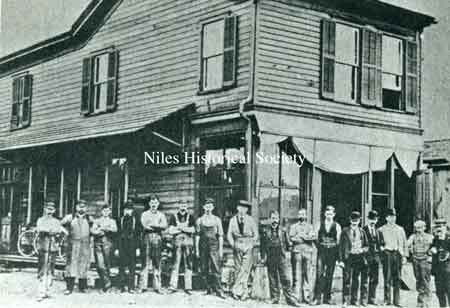

"In 1870 when father was eleven years old, his first job

was in a shoe store in Niles, Ohio. Back of the shoe store was

a work shop equipped with tools which exercised a strange fascination

upon him . When four years later his brother Charles came into

the store, the two boys began in earnest to experiment in making

things in their spare time. They next worked for Thad Ackley,

a jeweler in Warren, Ohio, who possessed an experimental turn

of mind and encouraged their mechanical ingenuity”.

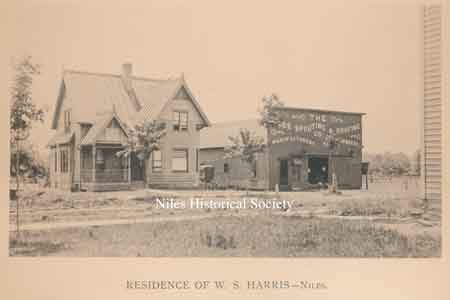

“Father then became a watch

inspector for a railway company. During this time he worked with

Charles on developing s twenty-four hour clock. Next they made

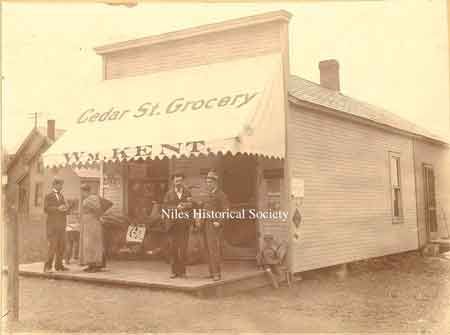

a nail feeder. In 1889 they became Niles’ only jeweler,

but the business was too small to take the full time of both of

them. Consequently, they had ample opportunity for research and

invention, The jewelry store had a back room, which they quickly

converted into a work shop.”

“One day Charles Harris watched

the installation of a new platen press in the shop of a local

printer named Smith. Smith was very proud of his new press. Charles

remarked that it was fed by hand, Smith, quick to defend his press,

challenged Charles to perfect an automatic feeder.”

“Shortly after this, a wagon

drove up before the jewelry store with a device that looked like

a clothes wringer. When father saw this unloaded, he protested,

saying that it was certainly not his."”

The driver, however, insisted on

leaving it. Later Charles came into the shop, and rather sheepishly

told of his talk with Smith some time before, and said that he

had built an automatic feeder. The two brothers laughed heartily

“at the joke on Smith”.”

“One day while Charles was

out, father had an inspiration, and with a yardstick, a saw blade,

and a rubber blanket, made a contrivance that completed the invention.

Soon sheets were running through at 15,000 per hour.”

“Their first press was a wooden

model. During the winter of 1890 they built an iron model in the

machine shop of a friend, who was located close to the jewelry

store. Whenever some part of the equipment in the machine shop

was not busy, the brothers were permitted to use it. The two worked

busily. In the summer of 1892 Charles, and later Father, went

to see the printing exhibits at the World’s Fair in Chicago.

Examination of the equipment there convinced them that they were

far ahead of anything so far developed; so they decided to go

into business.”

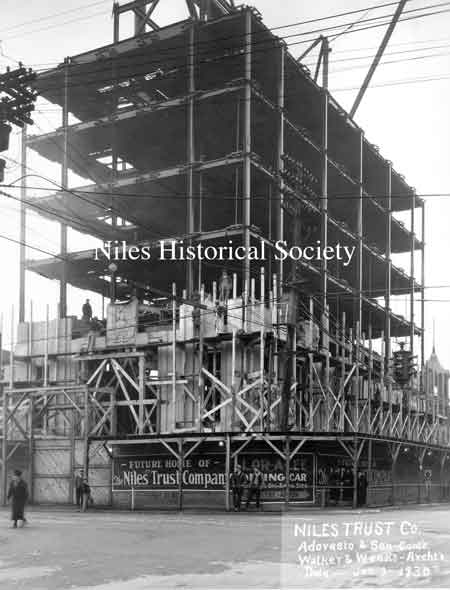

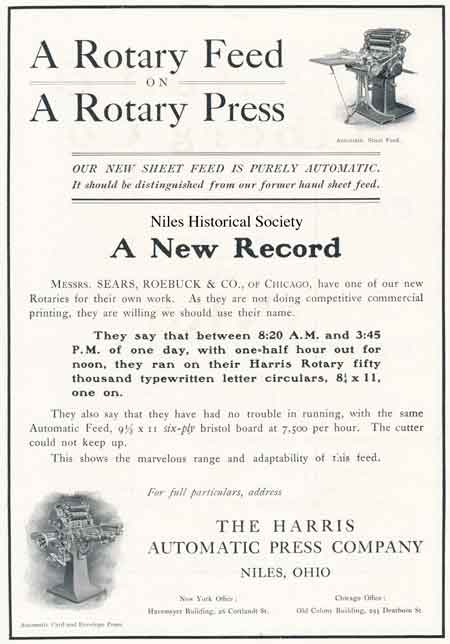

“Their first press of the

new company, which was incorporated in 1895, proved a failure,

and so they started all over again. In 1896 another machine was

completed. When it was offered for sale, no one believed the story

they told–the speed was so much greater than any press had

ever been able to run. When they offered it to the next man, they

made more modest claims with the result that they sold it.”

“Their first job was postcards.

They ran 12,500 postcards in fifty minutes. An all-tine record

up to then. Their second job was an envelope one, and this required

four months in order to perfect the machine so that it would feed

them. But, at last the difficulty was solved and the press accepted.

Press then followed press, in quick succession.”

“One day while erecting one

of their new automatic presses in a Cleveland plant, father heard

a pressman become very indignant at one of his operators. The

girl had neglected to trip the press when failing to feed a sheet.

The result was an impression on the rubber blanket. The next sheet

through was offset in reverse. Father and the pressman examined

the sheet closely and were particularly interested in the sharp

clear reproduction. Finally the pressman turned to him and said,

'If we could only print like that!' ”

“The result was that Father

and his brother set to work to make it possible to print like

that. First, they built a press with a plate cylinder, impression

cylinder, and two offset cylinders.This press proved that offset

printing was possible; but there were a good many things to learn

about it. Experiment followed experiment until finally the first

successful offset press was a reality. Each succeeding press has

been an improvement.”

“During the twenty-five years

since the installation of the first commercially successful offset

press in Pittsburgh, the offset process has come to play an ever-increasing

part in the graphic arts, The printers of America contributed

immeasurable to putting the offset process over."

The late Clifton A. Bostwick, who at one time resided

at 136 Salt Springs Road, Niles, worked for Harris Automatic as

an erector and trouble shooter in 1912. At that time Harris Automatic

Press Co. sold a press to Kline, Linderman and Bauer on New York

City and Bostwick was sent to setup the new press before a designated

deadline.

The press was shipped to Hoboken,

New Jersey and ferried across to New York City on the day the

longshoremen went on a one-day strike. The next day the longshoremen

unloaded the press, but that day the riggers went on strike and

another day of the delivery schedule was lost.

The press was finally delivered to a passenger elevator at Kline,

Linderman and Bauer Co. on Pearl St., near Wall St., in New York

City, where the elevator operator refused to transport it to the

17th floor destination.

After two days of coaxing, with

a bribe to make things legal, the elevator operator relented and

the delivery men and Bostwick proceeded to load the press on the

elevator. To erect the press, they had to use a 12-foot long I-beam.

The only way to get the I-beam to the 17th floor was to drop the

elevator to the basement and then tie the I-beam to the elevator

cable. Guess who rode on top of the elevator to steady the I-beam?

Well it wasn't one of the delivery boys. It was Clifton Bostwick!

There were also several crates of

press parts, but one crate in particular created a real problem.

The crate was larger than the elevator but smaller than the elevator

shaft. So, the delivery men ran wooden timbers across the elevator

shaft. Then, after moving the elevator up ten feet, they rolled

the crate onto the timbers; and, after dropping the elevator down,

used large ropes to secure the crate to the bottom of the elevator.

Then they took the crate up to the 17th floor.

The accomplishments of Charles and

Alfred Harris and the inequity of Clifton Bostwick are excellent

examples of Nilesites and their spirit Where there's a will, there's

a way!” |